Process Architecture

FRR is a suite of daemons that serve different functions. This document describes internal architecture of daemons, focusing their general design patterns, and especially how threads are used in the daemons that use them.

Overview

The fundamental pattern used in FRR daemons is an event loop. Some daemons use kernel threads. In these daemons, each kernel thread runs its own event loop. The event loop implementation is constructed to be thread safe and to allow threads other than its owning thread to schedule events on it. The rest of this document describes these two designs in detail.

Terminology

Because this document describes the architecture for kernel threads as well as the event system, a digression on terminology is in order here.

Historically Quagga’s loop system was viewed as an implementation of userspace

threading. Because of this design choice, the names for various datastructures

within the event system are variations on the term “thread”. The primary

datastructure that holds the state of an event loop in this system is called a

“threadmaster”. Events scheduled on the event loop - what would today be called

an ‘event’ or ‘task’ in systems such as libevent - are called “threads” and the

datastructure for them is struct event. To add to the confusion, these

“threads” have various types, one of which is “event”. To hopefully avoid some

of this confusion, this document refers to these “threads” as a ‘task’ except

where the datastructures are explicitly named. When they are explicitly named,

they will be formatted like this to differentiate from the conceptual

names. When speaking of kernel threads, the term used will be “pthread” since

FRR’s kernel threading implementation uses the POSIX threads API.

Event Architecture

This section presents a brief overview of the event model as currently implemented in FRR. This doc should be expanded and broken off into its own section. For now it provides basic information necessary to understand the interplay between the event system and kernel threads.

The core event system is implemented in lib/event.c and

lib/frrevent.h. The primary

structure is struct event_loop, hereafter referred to as a

threadmaster. A threadmaster is a global state object, or context, that

holds all the tasks currently pending execution as well as statistics on tasks

that have already executed. The event system is driven by adding tasks to this

data structure and then calling a function to retrieve the next task to

execute. At initialization, a daemon will typically create one

threadmaster, add a small set of initial tasks, and then run a loop to

fetch each task and execute it.

These tasks have various types corresponding to their general action. The types

are given by integer macros in frrevent.h and are:

EVENT_READTask which waits for a file descriptor to become ready for reading and then executes.

EVENT_WRITETask which waits for a file descriptor to become ready for writing and then executes.

EVENT_TIMERTask which executes after a certain amount of time has passed since it was scheduled.

EVENT_EVENTGeneric task that executes with high priority and carries an arbitrary integer indicating the event type to its handler. These are commonly used to implement the finite state machines typically found in routing protocols.

EVENT_READYType used internally for tasks on the ready queue.

EVENT_UNUSEDType used internally for

struct eventobjects that aren’t being used. The event system poolsstruct eventto avoid heap allocations; this is the type they have when they’re in the pool.EVENT_EXECUTEJust before a task is run its type is changed to this. This is used to show

Xas the type in the output ofshow event cpu.

The programmer never has to work with these types explicitly. Each type of task

is created and queued via special-purpose functions (actually macros, but

irrelevant for the time being) for the specific type. For example, to add a

EVENT_READ task, you would call

event_add_read(struct event_loop *master, int (*handler)(struct event *), void *arg, int fd, struct event **ref);

The struct event is then created and added to the appropriate internal

datastructure within the threadmaster. Note that the READ and

WRITE tasks are independent - a READ task only tests for

readability, for example.

The Event Loop

To use the event system, after creating a threadmaster the program adds an

initial set of tasks. As these tasks execute, they add more tasks that execute

at some point in the future. This sequence of tasks drives the lifecycle of the

program. When no more tasks are available, the program dies. Typically at

startup the first task added is an I/O task for VTYSH as well as any network

sockets needed for peerings or IPC.

To retrieve the next task to run the program calls event_fetch().

event_fetch() internally computes which task to execute next based on

rudimentary priority logic. Events (type EVENT_EVENT) execute with the

highest priority, followed by expired timers and finally I/O tasks (type

EVENT_READ and EVENT_WRITE). When scheduling a task a function and an

arbitrary argument are provided. The task returned from event_fetch() is

then executed with event_call().

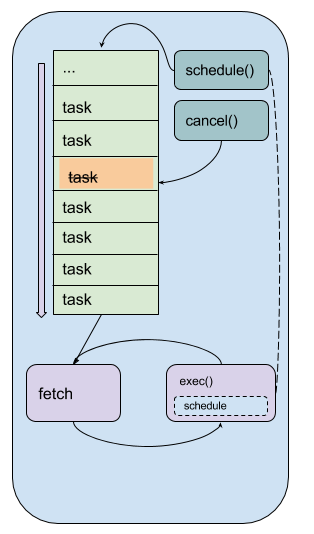

The following diagram illustrates a simplified version of this infrastructure.

Lifecycle of a program using a single threadmaster.

The series of “task” boxes represents the current ready task queue. The various other queues for other types are not shown. The fetch-execute loop is illustrated at the bottom.

Mapping the general names used in the figure to specific FRR functions:

taskisstruct event *fetchisevent_fetch()exec()isevent_call()cancel()isevent_cancel()schedule()is any of the various task-specificevent_add_*functions

Adding tasks is done with various task-specific function-like macros. These

macros wrap underlying functions in event.c to provide additional

information added at compile time, such as the line number the task was

scheduled from, that can be accessed at runtime for debugging, logging and

informational purposes. Each task type has its own specific scheduling function

that follow the naming convention event_add_<type>; see frrevent.h

for details.

There are some gotchas to keep in mind:

I/O tasks are keyed off the file descriptor associated with the I/O operation. This means that for any given file descriptor, only one of each type of I/O task (

EVENT_READandEVENT_WRITE) can be scheduled. For example, scheduling two write tasks one after the other will overwrite the first task with the second, resulting in total loss of the first task and difficult bugs.Timer tasks are only as accurate as the monotonic clock provided by the underlying operating system.

Memory management of the arbitrary handler argument passed in the schedule call is the responsibility of the caller.

Kernel Thread Architecture

Efforts have begun to introduce kernel threads into FRR to improve performance and stability. Naturally a kernel thread architecture has long been seen as orthogonal to an event-driven architecture, and the two do have significant overlap in terms of design choices. Since the event model is tightly integrated into FRR, careful thought has been put into how pthreads are introduced, what role they fill, and how they will interoperate with the event model.

Design Overview

Each kernel thread behaves as a lightweight process within FRR, sharing the same process memory space. On the other hand, the event system is designed to run in a single process and drive serial execution of a set of tasks. With this consideration, a natural choice is to implement the event system within each kernel thread. This allows us to leverage the event-driven execution model with the currently existing task and context primitives. In this way the familiar execution model of FRR gains the ability to execute tasks simultaneously while preserving the existing model for concurrency.

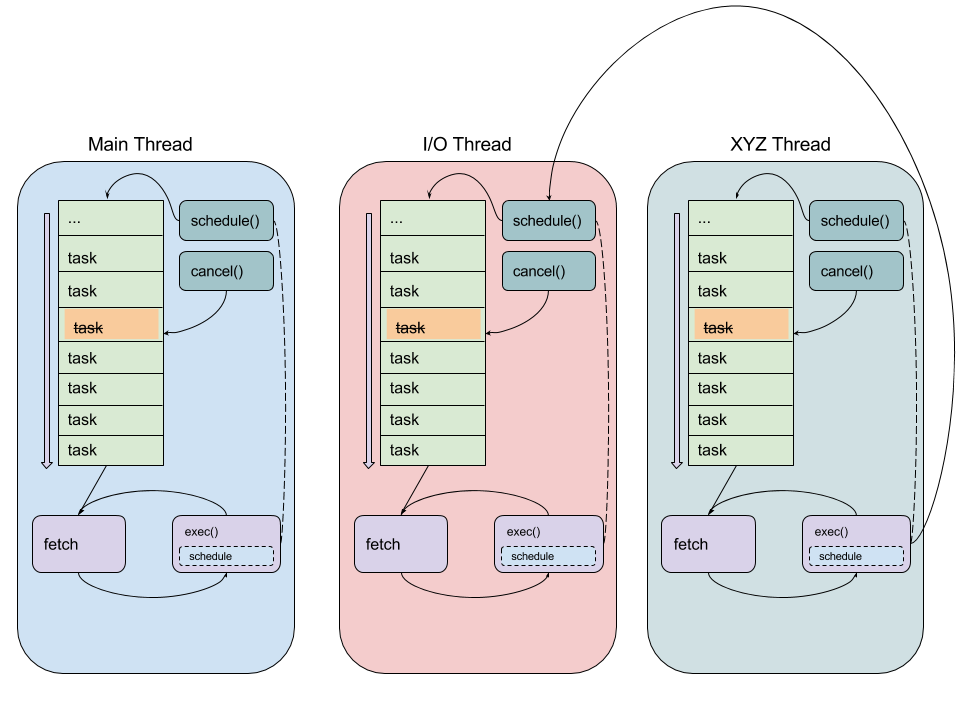

The following figure illustrates the architecture with multiple pthreads, each

running their own threadmaster-based event loop.

Lifecycle of a program using multiple pthreads, each running their own

threadmaster

Each roundrect represents a single pthread running the same event loop

described under Event Architecture. Note the arrow from the exec()

box on the right to the schedule() box in the middle pthread. This

illustrates code running in one pthread scheduling a task onto another

pthread’s threadmaster. A global lock for each threadmaster is used to

synchronize these operations. The pthread names are examples.

Kernel Thread Wrapper

The basis for the integration of pthreads and the event system is a lightweight

wrapper for both systems implemented in lib/frr_pthread.[ch]. The

header provides a core datastructure, struct frr_pthread, that encapsulates

structures from both POSIX threads and event.c, frrevent.h.

In particular, this

datastructure has a pointer to a threadmaster that runs within the pthread.

It also has fields for a name as well as start and stop functions that have

signatures similar to the POSIX arguments for pthread_create().

Calling frr_pthread_new() creates and registers a new frr_pthread. The

returned structure has a pre-initialized threadmaster, and its start

and stop functions are initialized to defaults that will run a basic event

loop with the given threadmaster. Calling frr_pthread_run() starts the thread

with the start function. From there, the model is the same as the regular

event model. To schedule tasks on a particular pthread, simply use the regular

event.c functions as usual and provide the threadmaster pointed to

from the frr_pthread. As part of implementing the wrapper, the

event.c functions were made thread-safe. Consequently, it is safe to

schedule events on a threadmaster belonging both to the calling thread as

well as any other pthread. This serves as the basis for inter-thread

communication and boils down to a slightly more complicated method of message

passing, where the messages are the regular task events as used in the

event-driven model. The only difference is thread cancellation, which requires

calling event_cancel_async() instead of event_cancel() to cancel a task

currently scheduled on a threadmaster belonging to a different pthread.

This is necessary to avoid race conditions in the specific case where one

pthread wants to guarantee that a task on another pthread is cancelled before

proceeding.

In addition, the existing commands to show statistics and other information for

tasks within the event driven model have been expanded to handle multiple

pthreads; running show event cpu will display the usual event

breakdown, but it will do so for each pthread running in the program. For

example, BGPD runs a dedicated I/O pthread and shows the following

output for show event cpu:

frr# show event cpu

Event statistics for bgpd:

Showing statistics for pthread main

------------------------------------

CPU (user+system): Real (wall-clock):

Active Runtime(ms) Invoked Avg uSec Max uSecs Avg uSec Max uSecs Type Thread

0 1389.000 10 138900 248000 135549 255349 T subgroup_coalesce_timer

0 0.000 1 0 0 18 18 T bgp_startup_timer_expire

0 850.000 18 47222 222000 47795 233814 T work_queue_run

0 0.000 10 0 0 6 14 T update_subgroup_merge_check_thread_cb

0 0.000 8 0 0 117 160 W zclient_flush_data

2 2.000 1 2000 2000 831 831 R bgp_accept

0 1.000 1 1000 1000 2832 2832 E zclient_connect

1 42082.000 240574 174 37000 178 72810 R vtysh_read

1 152.000 1885 80 2000 96 6292 R zclient_read

0 549346.000 2997298 183 7000 153 20242 E bgp_event

0 2120.000 300 7066 14000 6813 22046 T (bgp_holdtime_timer)

0 0.000 2 0 0 57 59 T update_group_refresh_default_originate_route_map

0 90.000 1 90000 90000 73729 73729 T bgp_route_map_update_timer

0 1417.000 9147 154 48000 132 61998 T bgp_process_packet

300 71807.000 2995200 23 3000 24 11066 T (bgp_connect_timer)

0 1894.000 12713 148 45000 112 33606 T (bgp_generate_updgrp_packets)

0 0.000 1 0 0 105 105 W vtysh_write

0 52.000 599 86 2000 138 6992 T (bgp_start_timer)

1 1.000 8 125 1000 164 593 R vtysh_accept

0 15.000 600 25 2000 15 153 T (bgp_routeadv_timer)

0 11.000 299 36 3000 53 3128 RW bgp_connect_check

Showing statistics for pthread BGP I/O thread

----------------------------------------------

CPU (user+system): Real (wall-clock):

Active Runtime(ms) Invoked Avg uSec Max uSecs Avg uSec Max uSecs Type Thread

0 1611.000 9296 173 13000 188 13685 R bgp_process_reads

0 2995.000 11753 254 26000 182 29355 W bgp_process_writes

Showing statistics for pthread BGP Keepalives thread

-----------------------------------------------------

CPU (user+system): Real (wall-clock):

Active Runtime(ms) Invoked Avg uSec Max uSecs Avg uSec Max uSecs Type Thread

No data to display yet.

Attentive readers will notice that there is a third thread, the Keepalives

thread. This thread is responsible for – surprise – generating keepalives for

peers. However, there are no statistics showing for that thread. Although the

pthread uses the frr_pthread wrapper, it opts not to use the embedded

threadmaster facilities. Instead it replaces the start and stop

functions with custom functions. This was done because the threadmaster

facilities introduce a small but significant amount of overhead relative to the

pthread’s task. In this case since the pthread does not need the event-driven

model and does not need to receive tasks from other pthreads, it is simpler and

more efficient to implement it outside of the provided event facilities. The

point to take away from this example is that while the facilities to make using

pthreads within FRR easy are already implemented, the wrapper is flexible and

allows usage of other models while still integrating with the rest of the FRR

core infrastructure. Starting and stopping this pthread works the same as it

does for any other frr_pthread; the only difference is that event

statistics are not collected for it, because there are no events.

Notes on Design and Documentation

Because of the choice to embed the existing event system into each pthread within FRR, at this time there is not integrated support for other models of pthread use such as divide and conquer. Similarly, there is no explicit support for thread pooling or similar higher level constructs. The currently existing infrastructure is designed around the concept of long-running worker threads responsible for specific jobs within each daemon. This is not to say that divide and conquer, thread pooling, etc. could not be implemented in the future. However, designs in this direction must be very careful to take into account the existing codebase. Introducing kernel threads into programs that have been written under the assumption of a single thread of execution must be done very carefully to avoid insidious errors and to ensure the program remains understandable and maintainable.

In keeping with these goals, future work on kernel threading should be extensively documented here and FRR developers should be very careful with their design choices, as poor choices tightly integrated can prove to be catastrophic for development efforts in the future.